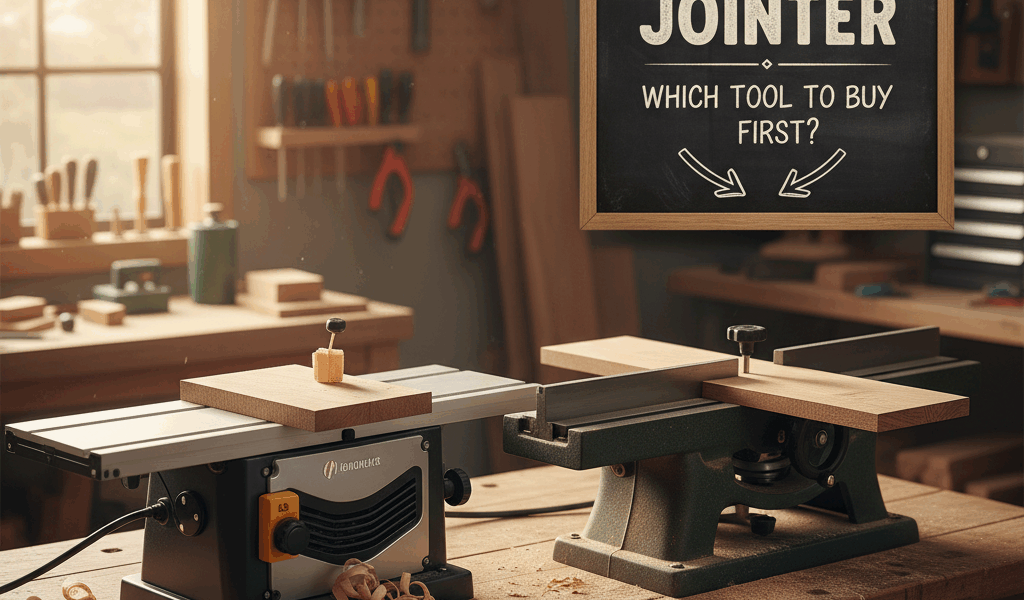

Planers and jointers serve different primary functions in dimensioning rough lumber. Understanding what each machine does—and can’t do—helps you decide which tool to buy first when budget limits purchasing both simultaneously.

What a Jointer Does

A jointer creates one flat face and one edge perpendicular to that face. The machine has two tables—infeed and outfeed—with a cylindrical cutterhead between them. The infeed table sits slightly lower than the cutterhead knives. As you push wood across the cutterhead, the knives remove material, and the outfeed table (level with the knife arc) supports the freshly cut surface.

The fence controls the edge jointing operation. Set the fence perpendicular to the tables, and the resulting edge is square to the jointed face. The jointer makes one surface flat and one edge perpendicular—it doesn’t make boards a specific thickness.

What a Planer Does

A planer makes boards uniform thickness. The machine has a flat bed with a cutterhead above it. Feed rollers pull the board through, and the cutterhead removes material from the top surface. The distance between the bed and cutterhead determines finished thickness.

The planer requires one flat face to start. That face registers against the bed while the cutterhead machines the opposite face parallel. If the starting face is warped, the planer produces a board with two parallel faces that are both warped. The planer can’t flatten warped boards—it only makes them uniformly thick.

The Complete Dimensioning Process

Proper dimensioning requires both machines working together:

- Joint one face flat on the jointer

- Joint one edge perpendicular to that face

- Run the board through the planer with the jointed face down to create a parallel top face

- Rip the board to final width at the table saw, removing the rough edge

This four-step process produces boards with two flat, parallel faces and two straight, parallel edges at your desired dimensions.

Working Without a Jointer

You can flatten one face using hand planes, a router sled, or by purchasing S2S (surfaced two sides) lumber that’s already been jointed and planed. The hand plane method requires skill and time but produces good results. A router sled with a flat reference surface works but is slow for large boards.

Purchasing S2S lumber eliminates the jointer step but costs more and limits you to available thicknesses. You’ll still want a planer to reduce S2S lumber to final thickness or to clean up surfaces after the lumber has acclimated to your shop.

Working Without a Planer

You can thickness boards with hand planes, but this requires significant time and skill. Each board takes 15-30 minutes to thickness by hand versus 1-2 minutes with a planer. For small projects, hand thicknessing is feasible. For larger work, it becomes impractical.

Purchasing S4S (surfaced four sides) lumber provides dimensioned boards but severely limits project flexibility. You’re constrained to standard thicknesses (usually 3/4 inch or 1 inch nominal) and pay premium prices. You also can’t dimension rough lumber, which offers the best wood selection and value.

Which to Buy First

Most woodworkers benefit more from buying a planer first. Here’s why:

A planer lets you thickness boards to any dimension, which is essential for most projects. You can work around not having a jointer by purchasing S2S lumber or using alternative flattening methods. You can’t effectively work around not having a planer without resorting to hand tools or being stuck with standard lumber thicknesses.

Planers also handle larger boards than jointers. A 12-inch planer processes boards up to 12 inches wide. A 6-inch jointer (the most common home shop size) only handles 6-inch-wide boards. For wider boards, you need alternative flattening methods anyway.

The Jointer-First Argument

Some woodworkers argue for buying a jointer first because you must flatten one face before the planer is useful. This logic makes sense but assumes you can’t flatten faces by alternative methods.

If you primarily work with rough lumber and don’t want to hand-plane or build router sleds, a jointer first makes sense. The jointer provides the flat reference surface needed for effective planer use.

Cost Considerations

A 12-inch benchtop planer costs $300-500 for quality models. These handle the majority of home shop work adequately. Larger planers with helical cutterheads run $800-2,000 but aren’t necessary for most users.

A 6-inch jointer costs $300-600 for benchtop models and $600-1,200 for floor-standing versions. An 8-inch jointer starts at $800 and reaches $1,500-2,500 for quality machines. The 6-inch capacity limitation frustrates many users, but 8-inch jointers cost significantly more.

For budget-constrained shops, buying a good planer ($400-500) leaves more money for other essential tools than buying a jointer first. You can address the flattening requirement with less expensive hand tools or techniques.

Space Requirements

Planers need floor space for their footprint plus infeed and outfeed clearance. A 12-inch planer requires approximately 8 feet of total length including feed space. Benchtop models can be stored when not in use, freeing floor space.

Jointers need similar length clearance but the floor-standing base makes them less mobile. A 6-inch jointer requires 6-8 feet total length. Most woodworkers leave jointers in place rather than moving them for storage.

In space-limited shops, benchtop planers offer better flexibility through mobility and storage options.

Long-Term Solution

The ideal situation is owning both machines. Start with whichever machine best addresses your immediate needs and working style. Add the second machine when budget permits.

If you mostly work with construction lumber and sheet goods, neither machine is urgent. If you’re building furniture from rough lumber, plan on acquiring both within your first year of serious woodworking.

Alternative: Combo Machines

Some manufacturers offer jointer-planer combination machines. These provide both functions in one unit, saving cost and floor space. The compromise is setup time when switching between functions and sometimes reduced capacity compared to separate machines.

Combo machines cost $1,200-2,500 depending on capacity and quality. For small shops where space is critical, they offer both capabilities at less than the cost of two separate machines. The switching time matters less for hobby woodworkers than production shops.

Used Equipment Option

Used planers and jointers offer good value if you find well-maintained machines. Check for worn ways on jointers (the flat surfaces the tables ride on) and worn feed rollers on planers. Either problem requires expensive repairs.

A used 6-inch jointer in good condition costs $200-400—half the new price. A used 12-inch planer runs $200-350 versus $400-500 new. The savings let you acquire both machines sooner than buying new.

Recommended Woodworking Tools

HURRICANE 4-Piece Wood Chisel Set – $13.99

CR-V steel beveled edge blades for precision carving.

GREBSTK 4-Piece Wood Chisel Set – $13.98

Sharp bevel edge bench chisels for woodworking.

As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases.